Muhammad

Muhammad | |

|---|---|

مُحَمَّد | |

"Muhammad, the Messenger of God" inscribed on the gates of the Prophet's Mosque, Medina | |

| Personal life | |

| Born | c. 570 CE (53 BH)[1] Mecca, Hejaz, Arabia |

| Died | 8 June 632 CE (11 AH; aged 61–62) |

| Resting place | Green Dome at the Prophet's Mosque, Medina, Arabia 24°28′03″N 39°36′41″E / 24.46750°N 39.61139°E |

| Spouse | See wives of Muhammad |

| Children | See children of Muhammad |

| Parents |

|

| Known for | Establishing Islam |

| Other names | Rasūl Allāh (lit. 'Messenger of God') See names and titles of Muhammad |

| Relatives | Ahl al-Bayt (lit. 'People of the House') See family tree of Muhammad |

| Part of a series on |

| Muhammad |

|---|

Muhammad[a] (c. 570 – 8 June 632 CE)[b] was an Arab religious and political leader and the founder of Islam.[c] According to Islam, he was a prophet who was divinely inspired to preach and confirm the monotheistic teachings of Adam, Noah, Abraham, Moses, Jesus, and other prophets. He is believed to be the Seal of the Prophets in Islam, and along with the Quran, his teachings and normative examples form the basis for Islamic religious belief.

Muhammad was born c. 570 CE in Mecca. He was the son of Abdullah ibn Abd al-Muttalib and Amina bint Wahb. His father, Abdullah, the son of Quraysh tribal leader Abd al-Muttalib ibn Hashim, died around the time Muhammad was born. His mother Amina died when he was six, leaving Muhammad an orphan. He was raised under the care of his grandfather, Abd al-Muttalib, and paternal uncle, Abu Talib. In later years, he would periodically seclude himself in a mountain cave named Hira for several nights of prayer. When he was 40, c. 610, Muhammad reported being visited by Gabriel in the cave and receiving his first revelation from God. In 613,[2] Muhammad started preaching these revelations publicly,[3] proclaiming that 'God is One', that complete 'submission' (Islām) to God (Allāh) is the right way of life (dīn),[4] and that he was a prophet and messenger of God, similar to the other prophets in Islam.[5]

Muhammad's followers were initially few in number, and experienced persecution by Meccan polytheists for 13 years. To escape ongoing persecution, he sent some of his followers to Abyssinia in 615, before he and his followers migrated from Mecca to Medina (then known as Yathrib) later in 622. This event, the Hijrah, marks the beginning of the Islamic calendar, also known as the Hijri calendar. In Medina, Muhammad united the tribes under the Constitution of Medina. In December 629, after eight years of intermittent fighting with Meccan tribes, Muhammad gathered an army of 10,000 Muslim converts and marched on the city of Mecca. The conquest went largely uncontested, and Muhammad seized the city with minimal casualties. In 632, a few months after returning from the Farewell Pilgrimage, he fell ill and died. By the time of his death, most of the Arabian Peninsula had converted to Islam.

The revelations (waḥy) that Muhammad reported receiving until his death form the verses (āyah) of the Quran, upon which Islam is based, are regarded by Muslims as the verbatim word of God and his final revelation. Besides the Quran, Muhammad's teachings and practices, found in transmitted reports, known as hadith, and in his biography (sīrah), are also upheld and used as sources of Islamic law. Apart from Islam, Muhammad is regarded as one of the prophets in the Druze faith and a Manifestation of God in the Baháʼí Faith.

Biographical sources

Early biographies

The most striking point about Muhammad's life and early Islamic history is; The information that forms the basis for writing histories is an irregular product of the storytelling culture and emerges as an increasing development of details over the centuries. The narratives were initially in the form of heroic epics called "maghāzī", but by adding and editing details they turned into compilations of sirahs.[6] Lawrence Conrad examines the biography books written in the early post-oral period and sees that a time period of 85 years is exhibited in these works regarding the date of Muhammad's birth. Conrad defines this as "the fluidity (evolutionary process) is still continuing" in the story.[7]

Important sources regarding Muhammad's life may be found in the works by writers of the 2nd and 3rd centuries of the Hijri era (mostly overlapping with the 8th and 9th centuries CE respectively).[8] These are traditional Muslim biographies that provide information about the life of Muhammad.[9] The earliest written sira is Ibn Ishaq's lost Life of God's Messenger written c. 767 (150 AH) though sira survives as extensive excerpts in works by Ibn Hisham and to a lesser extent by Al-Tabari[10][11] with Ibn Hisham's note that he omitted matters from Ibn Ishaq's biography that "would distress certain people".[12] Another early historical source is the history of Muhammad's campaigns (maghāzī) by al-Waqidi (d. 207 AH), and the work of Waqidi's secretary Ibn Sa'd al-Baghdadi (d. 230 AH).[8]

Western historians describe the purpose of these early biographies as largely to convey a message, rather than to strictly and accurately record history.[13] Although these compilations are indispensable in terms of rhetorical language and religious sermons in Islam, they are not valuable enough to be considered a source of judgment for fiqh, though some scholars may accept these early biographies as authentic.[10] The narratives are incompatible with today's historian logic, for example, no source is mentioned for the information in Waqidi's work.[14] The values attributed to stories pointing to different geographical regions such as North of Arabia may lead to controversial situations in terms of cultural heritage and economic sharings today.

Recent studies have led scholars to distinguish between traditions touching legal matters and purely historical events. In the legal group, traditions could have been subject to invention while historic events, aside from exceptional cases, may have been subject only to "tendential shaping".[15] Other scholars have criticized the reliability of this method, suggesting that one cannot neatly divide traditions into purely legal and historical categories.[16]

Qur'an

The Quran is the central religious text of Islam and Muslims believe it represents the unaltered words of God revealed by the archangel Gabriel to Muhammad sent down during his life, hence it must be a text contemporary to Muhammad and contain the most accurate information for this period.[17][18] [19][20][21] Although the Quran appears to address a messenger named Muhammad in a small number of verses (e.g., 3:144), it actually provides little concrete information for Muhammad's chronological biography; most Quranic verses do not provide significant historical context and timeline.[22][23] Qur'an speaks of a pilgrimage sanctuary that is associated with the “valley of Mecca” and the Kaʿbah (e.g., 2:124–129, 5:97, 48:24–25). Certain verses assume that Muhammad and his followers dwell at a settlement called al-madīnah (“the town”) or Yathrib (e.g., 33:13, 60) after having previously been ousted by their unbelieving foes. Other passages mention military encounters between Muhammad’s followers and the unbelievers at a place called Badr at 3:123.[24] However, the text provides no dates for any of the historical events, and almost none of the messenger’s contemporaries are mentioned by name (a rare exception is at 33:37).

In 1972, in a mosque in the city of Sana'a, Yemen, manuscripts "consisting of 12,000 pieces" were discovered that were later proven to be the oldest yet largest Quranic text known to exist at the time containing palimpsests washed-off yet underlying text is still barely visible.[25] Gerd R. Puin has noted unconventional verse orderings, minor textual variations, and rare styles of orthography, and suggested that some of the parchments were palimpsests reused which led GR Puin to believe that it was an evolving text rather than a fixed one.[26] In 2015, a single folio of a very early Quran, dating back to 1370 years earlier, was discovered in the library of the University of Birmingham written in Hijazi script,[27] and caused excitement amongst believers because of its potential overlapping with the dominant tradition over the lifetime of Muhammad c. 570 to 632 CE[28] and used as evidence to support conventional wisdom and to refute the revisionists' views[29] that expresses findings and views different from the traditional approach to the early history of the Quran and Islam.

Rasm: "ٮسم الله الرحمں الرحىم"

Nonetheless, the content of the Quran itself -considering that it is connected with the life of Muhammad-, may provides some data for the earliest dates of its some passages writings; sources based on archaeological data give the construction date of Masjid al-Haram, an architectural work mentioned 16 times in the Quran, as 78 AH[30] an additional finding that sheds light on the evolutionary history of the Quran which is known to continue even during the time of Hajjaj,[31][32] in a similar situation that can be seen with al-Aksa, though different suggestions have been put forward to explain.[d]

Hadith

Other important sources include the hadith collections, accounts of verbal and physical teachings and traditions attributed to Muhammad. Hadiths were compiled several generations after his death by Muslims including Muhammad al-Bukhari, Muslim ibn al-Hajjaj, Muhammad ibn Isa at-Tirmidhi, Abd ar-Rahman al-Nasai, Abu Dawood, Ibn Majah, Malik ibn Anas, al-Daraqutni.[41][42]

Muslim scholars have typically placed a greater emphasis on the hadith instead of the biographical literature, since hadith maintain a traditional chain of transmission (isnad); the lack of such a chain for the biographical literature makes it unverifiable in their eyes.[43] The hadiths generally present an idealized view of Muhammad.[44] Western scholars have expressed skepticism regarding the verifiability of these chains of transmission. It is widely believed by Western scholars that there was widespread fabrication of hadith during the early centuries of Islam to support certain theological and legal positions,[45][44] and it has been suggested that it is "very likely that a considerable number of hadiths that can be found in the hadith collections did not actually originate with the Prophet".[44] In addition, the meaning of a hadith may have drifted from its original telling to when it was finally written down, even if the chain of transmission is authentic.[16] Overall, some Western academics have cautiously viewed the hadith collections as accurate historical sources,[41] while the "dominant paradigm" in Western scholarship is to consider their reliability suspect.[45] Scholars such as Wilferd Madelung do not reject the hadith which have been compiled in later periods, but judge them in their historical context.[46]

Meccan years

Early life

| Timeline of Muhammad's life | ||

|---|---|---|

| Important dates and locations in the life of Muhammad | ||

| Date | Age | Event |

| c. 570 | – | Death of his father, Abdullah |

| c. 570 | 0 | Possible date of birth: 12 or 17 Rabi al Awal: in Mecca, Arabia |

| c. 577 | 6 | Death of his mother, Amina |

| c. 583 | 12–13 | His grandfather transfers him to Syria |

| c. 595 | 24–25 | Meets and marries Khadijah |

| c. 599 | 28–29 | Birth of Zainab, his first daughter, followed by: Ruqayyah, Umm Kulthum, and Fatima Zahra |

| 610 | 40 | Qur'anic revelation begins in the Cave of Hira on the Jabal an-Nour, the "Mountain of Light" near Mecca. At age 40, Angel Jebreel (Gabriel) was said to appear to Muhammad on the mountain and call him "the Prophet of Allah" |

| Begins in secret to gather followers in Mecca | ||

| c. 613 | 43 | Begins spreading message of Islam publicly to all Meccans |

| c. 614 | 43–44 | Heavy persecution of Muslims begins |

| c. 615 | 44–45 | Emigration of a group of Muslims to Ethiopia |

| c. 616 | 45–46 | Banu Hashim clan boycott begins |

| 619 | 49 | Banu Hashim clan boycott ends |

| The year of sorrows: Khadija (his wife) and Abu Talib (his uncle) die | ||

| c. 620 | 49–50 | Isra and Mi'raj (reported ascension to heaven to meet God) |

| 622 | 51–52 | Hijra, emigration to Medina (called Yathrib) |

| 624 | 53–54 | Battle of Badr |

| 625 | 54–55 | Battle of Uhud |

| 627 | 56–57 | Battle of the Trench (also known as the siege of Medina) |

| 628 | 57–58 | The Meccan tribe of Quraysh and the Muslim community in Medina sign a 10-year truce called the Treaty of Hudaybiyyah |

| 630 | 59–60 | Conquest of Mecca |

| 632 | 61–62 | Farewell pilgrimage, event of Ghadir Khumm, and death, in what is now Saudi Arabia |

Muhammad ibn Abdullah ibn Abd al-Muttalib ibn Hashim[47] was born in Mecca[48][1] c. 570,[1] and his birthday is believed to be in the month of Rabi' al-Awwal.[49] He belonged to the Banu Hashim clan of the Quraysh tribe, which was a dominant force in western Arabia.[50] While his clan was one of the more distinguished in the tribe, it seems to have experienced a lack of prosperity during his early years.[51][e] According to Muslim tradition, Muhammad was a hanif, someone who professed monotheism in pre-Islamic Arabia.[52] He is also claimed to have been a descendant of Ishmael, son of Abraham.[53]

The name Muhammad means "praiseworthy" in Arabic and it appears four times in the Quran.[54] He was also known as "al-Amin" (lit. 'faithful') when he was young; however, historians differ as to whether it was given by people as a reflection of his nature[55] or was simply a given name from his parents, i.e., a masculine form of his mother's name "Amina".[56] Muhammad acquired the kunya of Abu al-Qasim later in his life after the birth of his son Qasim, who died two years afterwards.[57]

Islamic tradition states that Muhammad's birth year coincided with the Year of the Elephant, when Abraha, the Aksumite viceroy in the former Himyarite Kingdom, unsuccessfully attempted to conquer Mecca.[58] Recent studies, however, challenge this notion, as other evidence suggests that the expedition, if it had occurred, would have transpired substantially before Muhammad's birth.[59] Later Muslim scholars presumably linked Abraha's renowned name to the narrative of Muhammad's birth to elucidate the unclear passage about "the men of elephants" in Quran 105:1–5.[60][61] The Oxford Handbook of Late Antiquity deems the tale of Abraha's war elephant expedition as a myth.[62]

Muhammad's father, Abdullah, died almost six months before he was born.[63] Muhammad then stayed with his foster mother, Halima bint Abi Dhu'ayb, and her husband until he was two years old. At the age of six, Muhammad lost his biological mother Amina to illness and became an orphan.[64][65][66] For the next two years, until he was eight years old, Muhammad was under the guardianship of his paternal grandfather, Abd al-Muttalib, until the latter's death. He then came under the care of his uncle, Abu Talib,[67] the new leader of the Banu Hashim.[67] Abu Talib's brothers assisted with Muhammad's learning – Hamza, the youngest, trained Muhammad in archery, swordsmanship, and martial arts. Another uncle, Abbas, provided Muhammad with a job leading caravans on the northern segment of the route to Syria.[68]

The historical record of Mecca during Muhammad's early life is limited and fragmentary, making it difficult to distinguish between fact and legend.[69] Several Islamic narratives relate that Muhammad, as a child, went on a trading trip to Syria with his uncle Abu Talib and met a monk named Bahira, who is said to have then foretold his prophethood.[70] There are multiple versions of the story with details that contradict each other.[71] All accounts of Bahira and his meeting with Muhammad have been considered fictitious by modern historians[72] as well as by some medieval Muslim scholars such as al-Dhahabi.[73]

Sometime later in his life, Muhammad proposed marriage to his cousin and first love, Fakhitah bint Abi Talib. But likely owing to his poverty, his proposal was rejected by her father, Abu Talib, who chose a more illustrious suitor.[74][75] When Muhammad was 25, his fortunes turned around; his business reputation caught the attention of his 40-year-old distant relative Khadija, a wealthy businesswoman who had staked out a successful career as a merchant in the caravan trade industry. She asked him to take one of her caravans into Syria, after which she was so impressed by his competence in the expedition that she proposed marriage to him; Muhammad accepted her offer and remained monogamous with her until her death.[76][77][78]

In 605, the Quraysh decided to roof the Kaaba, which had previously consisted only of walls. A complete rebuild was needed to accommodate the new weight. Amid concerns about upsetting the deities, a man stepped forth with a pickaxe and exclaimed, "O goddess! Fear not! Our intentions are only for the best." With that, he began demolishing it. The anxious Meccans awaited divine retribution overnight, but his unharmed continuation the next day was seen as a sign of heavenly approval. According to a narrative collected by Ibn Ishaq, when it was time to reattach the Black Stone, a dispute arose over which clan should have the privilege. It was determined that the first person to step into the Kaaba's court would arbitrate. Muhammad took on this role, asking for a cloak. He placed the stone on it, guiding clan representatives to jointly elevate it to its position. He then personally secured it within the wall.[80][81]

Beginnings of the Quran

The financial security Muhammad enjoyed from Khadija, his wealthy wife, gave him plenty of free time to spend in solitude in the cave of Hira.[82][83] According to Islamic tradition, in 610, when he was 40 years old, the angel Gabriel appeared to him during his visit to the cave.[1] The angel showed him a cloth with Quranic verses on it and instructed him to read. When Muhammad confessed his illiteracy, Gabriel choked him forcefully, nearly suffocating him, and repeated the command. As Muhammad reiterated his inability to read, Gabriel choked him again in a similar manner. This sequence took place once more before Gabriel finally recited the verses, allowing Muhammad to memorize them.[84][85][86] These verses later constituted Quran 96:1-5.[87]

When Muhammad came to his senses, he felt scared; he started to think that after all of this spiritual struggle, he had been visited by a jinn, which made him no longer want to live. In desperation, Muhammad fled from the cave and began climbing up towards the top of the mountain to jump to his death. But when he reached the summit, he experienced another vision, this time seeing a mighty being that engulfed the horizon and stared back at Muhammad even when he turned to face a different direction. This was the spirit of revelation (rūḥ), which Muhammad later referred to as Gabriel; it was not a naturalistic angel, but rather a transcendent presence that resisted the ordinary limits of humanity and space.[88][89][90]

Frightened and unable to understand the experience, Muhammad hurriedly staggered down the mountain to his wife Khadija. By the time he got to her, he was already crawling on his hands and knees, shaking wildly and crying "Cover me!", as he thrust himself onto her lap. Khadija wrapped him in a cloak and tucked him in her arms until his fears dissipated. She had absolutely no doubts about his revelation; she insisted it was real and not a jinn.[88] Muhammad was also reassured by Khadija's Christian cousin Waraqah ibn Nawfal,[91] who jubilantly exclaimed "Holy! Holy! If you have spoken the truth to me, O Khadijah, there has come to him the great divinity who came to Moses aforetime, and lo, he is the prophet of his people."[92][93] Khadija instructed Muhammad to let her know if Gabriel returned. When he appeared during their private time, Khadija conducted tests by having Muhammad sit on her left thigh, right thigh, and lap, inquiring Muhammad if the being was still present each time. After Khadija removed her clothes with Muhammad on her lap, he reported that Gabriel left at that moment. Khadija thus told him to rejoice as she concluded it was not Satan but an angel visiting him.[94][95][91]

Muhammad's demeanor during his moments of inspiration frequently led to allegations from his contemporaries that he was under the influence of a jinn, a soothsayer, or a magician, suggesting that his experiences during these events bore resemblance to those associated with such figures widely recognized in ancient Arabia. Nonetheless, these enigmatic seizure events might have served as persuasive evidence for his followers regarding the divine origin of his revelations. Some historians posit that the graphic descriptions of Muhammad's condition in these instances are likely genuine, as they are improbable to have been concocted by later Muslims.[96][97]

Shortly after Waraqa's death, the revelations ceased for a period, causing Muhammad great distress and thoughts of suicide.[98] On one occasion, he reportedly climbed a mountain intending to jump off. However, upon reaching the peak, Gabriel appeared to him, affirming his status as the true Messenger of God. This encounter soothed Muhammad, and he returned home. Later, when there was another long break between revelations, he repeated this action, but Gabriel intervened similarly, calming him and causing him to return home.[99][100]

Muhammad was confident that he could distinguish his own thoughts from these messages.[101] The early Quranic revelations utilized approaches of cautioning non-believers with divine punishment, while promising rewards to believers. They conveyed potential consequences like famine and killing for those who rejected Muhammad's God and alluded to past and future calamities. The verses also stressed the imminent final judgment and the threat of hellfire for skeptics.[102] Due to the complexity of the experience, Muhammad was initially very reluctant to tell others about his revelations;[103] at first, he confided in only a few select family members and friends.[104] According to Muslim tradition, Muhammad's wife Khadija was the first to believe he was a prophet.[105] She was followed by Muhammad's ten-year-old cousin Ali ibn Abi Talib, close friend Abu Bakr, and adopted son Zayd.[105] As word of Muhammad's revelations continued to spread throughout the rest of his family, they became increasingly divided on the matter, with the youth and women generally believing in him, while most of the men in the elder generations were staunchly opposed.[106]

Opposition in Mecca

Around 613, Muhammad began to preach to the public;[3][107] many of his first followers were women, freedmen, servants, slaves, and other members of the lower social class.[106] These converts keenly awaited each new revelation from Muhammad; when he recited it, they all would repeat after him and memorize it, and the literate ones recorded it in writing.[108] Muhammad also introduced rituals to his group which included prayer (salat) with physical postures that embodied complete surrender (islam) to God, and almsgiving (zakat) as a requirement of the Muslim community (ummah).[109] By this point, Muhammad's religious movement was known as tazakka ('purification').[110][111]

Initially, he had no serious opposition from the inhabitants of Mecca, who were indifferent to his proselytizing activities, but when he started to attack their beliefs, tensions arose.[112][113][114][115] The Quraysh challenged him to perform miracles, such as bringing forth springs of water, yet he declined, reasoning that the regularities of nature already served as sufficient proof of God's majesty. Some satirized his lack of success by wondering why God had not bestowed treasure upon him. Others called on him to visit Paradise and return with tangible parchment scrolls of the Quran. But Muhammad asserted that the Quran, in the form he conveyed it, was already an extraordinary proof.[116][117]

According to Amr ibn al-As, several of the Quraysh gathered at Hijr and discussed how they had never faced such serious problems as they were facing from Muhammad. They said that he had derided their culture, denigrated their ancestors, scorned their faith, shattered their community, and cursed their gods. Sometime later, Muhammad came, kissing the Black Stone and performing the ritual tawaf. As Muhammad passed by them, they reportedly said hurtful things to him. The same happened when he passed by them a second time. On his third pass, Muhammad stopped and said, "Will you listen to me, O Quraysh? By Him (God), who holds my life in His hand, I bring you slaughter." They fell silent and told him to go home, saying that he was not a violent man. The next day, a number of Quraysh approached him, asking if he had said what they had heard from their companions. He answered yes, and one of them seized him by his cloak. Abu Bakr intervened, tearfully saying, "Would you kill a man for saying God is my Lord?" And they left him.[118][119][120]

The Quraysh attempted to entice Muhammad to quit preaching by giving him admission to the merchants' inner circle as well as an advantageous marriage, but he refused both of the offers.[121] A delegation of them then, led by the leader of the Makhzum clan, known by the Muslims as Abu Jahl, went to Muhammad's uncle Abu Talib, head of the Hashim clan and Muhammad's caretaker, giving him an ultimatum to disown Muhammad:[122][123]

"By God, we can no longer endure this vilification of our forefathers, this derision of our traditional values, this abuse of our gods. Either you stop Muhammad yourself, Abu Talib, or you must let us stop him. Since you yourself take the same position as we do, in opposition to what he’s saying, we will rid you of him."[124][125]

Abu Talib politely dismissed them at first, thinking it was just a heated talk. But as Muhammad grew more vocal, Abu Talib requested Muhammad to not burden him beyond what he could bear, to which Muhammad wept and replied that he would not stop even if they put the sun in his right hand and the moon in his left. When he turned around, Abu Talib called him and said, "Come back nephew, say what you please, for by God I will never give you up on any account."[126][127]

Quraysh delegation to Yathrib

The leaders of the Quraysh sent Nadr ibn al-Harith and Uqba ibn Abi Mu'ayt to Yathrib to seek the opinions of the Jewish rabbis regarding Muhammad. The rabbis advised them to ask Muhammad three questions: recount the tale of young men who ventured forth in the first age; narrate the story of a traveler who reached both the eastern and western ends of the earth; and provide details about the spirit. If Muhammad answered correctly, they stated, he would be a Prophet; otherwise, he would be a liar. When they returned to Mecca and asked Muhammad the questions, he told them he would provide the answers the next day. However, 15 days passed without a response from his God, leading to gossip among the Meccans and causing Muhammad distress. At some point later, the angel Gabriel came to Muhammad and provided him with the answers.[128][129]

In response to the first query, the Quran tells a story about a group of men sleeping in a cave (Quran 18:9–25), which scholars generally link to the legend of the Seven Sleepers of Ephesus. For the second query, the Quran speaks of Dhu al-Qarnayn, literally 'he of the two horns' (Quran 18:93–99), a tale that academics widely associate with the Alexander Romance.[130][131] As for the third query, concerning the nature of the spirit, the Quranic revelation asserted that it was beyond human comprehension. Neither the Jews who devised the questions nor the Quraysh who posed them to Muhammad converted to Islam upon receiving the answers.[129] Nadr and Uqba were later executed on Muhammad's orders after the Battle of Badr, while other captives were held for ransom. As Uqba pleaded, "But who will take care of my children, Muhammad?" Muhammad responded, "Hell!"[132]

Migration to Abyssinia and the incident of Satanic Verses

In 615, Muhammad sent some of his followers to emigrate to the Abyssinian Kingdom of Aksum and found a small colony under the protection of the Christian Ethiopian emperor Aṣḥama ibn Abjar.[51] Among those who departed were Umm Habiba, the daughter of one of the Quraysh chiefs, Abu Sufyan, and her husband.[133] The Quraysh then sent two men to retrieve them. Because leatherwork at the time was highly prized in Abyssinia, they gathered a lot of skins and transported them there so they could distribute some to each of the kingdom's generals. But the king firmly rejected their request.[134]

While Tabari and Ibn Hisham mentioned only one migration to Abyssinia, there were two sets according to Ibn Sa'd. Of these two, the majority of the first group returned to Mecca before the event of Hijrah, while the majority of the second group remained in Abyssinia at the time and went directly to Medina after the event of Hijrah. These accounts agree that persecution played a major role in Muhammad sending them there. According to W. Montgomery Watt, the episodes were more complex than the traditional accounts suggest; he proposes that there were divisions within the embryonic Muslim community, and that they likely went there to trade in competition with the prominent merchant families of Mecca. In Urwa's letter preserved by Tabari, these emigrants returned after the conversion to Islam of a number of individuals in positions such as Hamza and Umar.[135]

Along with many others,[136] Tabari recorded that Muhammad was desperate, hoping for an accommodation with his tribe. So, while he was in the presence of a number of Quraysh, after delivering verses mentioning three of their favorite deities (Quran 53:19–20), Satan put upon his tongue two short verses: "These are the high flying ones / whose intercession is to be hoped for." This led to a general reconciliation between Muhammad and the Meccans, and the Muslims in Abyssinia began to return home. However, the next day, Muhammad retracted these verses at the behest of Gabriel, claiming that they had been cast by Satan to his tongue and God had abrogated them. Instead, verses that revile those goddesses were then revealed.[137][f][g] The returning Muslims thus had to make arrangements for clan protection before they could re-enter Mecca.[51][138]

This Satanic verses incident was reported en masse and documented by nearly all of the major biographers of Muhammad in Islam's first two centuries,[139] which according to them corresponds to Quran 22:52. But since the rise of the hadith movement and systematic theology with its new doctrines, including the Ismah, which claimed that Muhammad was infallible and thus could not be fooled by Satan, the historical memory of the early community has been reevaluated. By the 20th century, Muslim scholars unanimously rejected this incident.[136] On the other hand, most European biographers of Muhammad recognize the veracity of this incident of satanic verses on the basis of the criterion of embarrassment. Historian Alfred T. Welch proposes that the period of Muhammad's turning away from strict monotheism was likely far longer but was later encapsulated in a story that made it much shorter and implicated Satan as the culprit.[135]

In 616, an agreement was established whereby all other Quraysh clans were to enforce a ban on the Banu Hashim, prohibiting trade and marriage with them.[140][141] Nevertheless, Banu Hashim members could still move around the town freely. Despite facing increasing verbal abuse, Muhammad continued to navigate the streets and engage in public debates without being physically harmed.[142] At a later point, a faction within Quraysh, sympathizing with Banu Hashim, initiated efforts to end the sanctions, resulting in a general consensus in 619 to lift the ban.[143][135]

Attempt to establish himself in Ta'if

In 619, Muhammad faced a period of sorrow. His wife, Khadija, a crucial source of his financial and emotional support, died.[144] In the same year, his uncle and guardian, Abu Talib, also died.[145][146] Despite Muhammad's persuasions to Abu Talib to embrace Islam on his deathbed, he clung to his polytheistic beliefs until the end.[147][146] Muhammad's other uncle, Abu Lahab, who succeeded the Banu Hashim clan leadership, was initially willing to provide Muhammad with protection. However, upon hearing from Muhammad that Abu Talib and Abd al-Muttalib were destined for hell due to not believing in Islam, he withdrew his support.[147][148]

Muhammad then went to Ta'if to try to establish himself in the city and gain aid and protection against the Meccans,[149][135][150] but he was met with a response: "If you are truly a prophet, what need do you have of our help? If God sent you as his messenger, why doesn't He protect you? And if Allah wished to send a prophet, couldn't He have found a better person than you, a weak and fatherless orphan?"[151] Realizing his efforts were in vain, Muhammad asked the people of Ta'if to keep the matter a secret, fearing that this would embolden the hostility of the Quraysh against him. However, instead of accepting his request, they pelted him with stones, injuring his limbs.[152] He eventually evaded this chaos and persecution by escaping to the garden of Utbah ibn Rabi'ah, a Meccan chief with a summer residence in Ta'if. Muhammad felt despair due to the unexpected rejection and hostility he received in the city; at this point, he realized he had no security or protection except from God, so he began praying. Shortly thereafter, Utbah's Christian slave Addas stopped by and offered grapes, which Muhammad accepted. By the end of the encounter, Addas felt overwhelmed and kissed Muhammad's head, hands, and feet in recognition of his prophethood.[153][154][155]

On Muhammad's return journey to Mecca, news of the events in Ta'if had reached the ears of Abu Jahl, and he said, "They did not allow him to enter Ta'if, so let us deny him entry to Mecca as well." Knowing the gravity of the situation, Muhammad asked a passing horseman to deliver a message to Akhnas ibn Shariq, a member of his mother's clan, requesting his protection so that he could enter in safety. But Akhnas declined, saying that he was only a confederate of the house of Quraysh. Muhammad then sent a message to Suhayl ibn Amir, who similarly declined on the basis of tribal principle. Finally, Muhammad dispatched someone to ask Mut'im ibn 'Adiy, the chief of the Banu Nawfal. Mut'im agreed, and after equipping himself, he rode out in the morning with his sons and nephews to accompany Muhammad to the city. When Abu Jahl saw him, he asked if Mut'im was simply giving him protection or if he had already converted to his religion. Mut'im replied, "Granting him protection, of course." Then Abu Jahl said, "We will protect whomever you protect."[156]

Isra' and Mi'raj

It is at this low point in Muhammad's life that the accounts in the Sīrah lay out the famous Isra' and Mi'raj. Nowadays, Isra' is believed by Muslims to be the journey of Muhammad from Mecca to Jerusalem, while Mi'raj is from Jerusalem to the heavens.[158] There is considered no substantial basis for the Mi'raj in the Quran, as the Quran does not address it directly.[159]

Verse 17:1 of the Quran recounts Muhammad's night journey from a revered place of prayer to the most distant place of worship. The Kaaba, holy enclosure in Mecca, is widely accepted as the starting point, but there is disagreement among Islamic traditions as to what constitutes "the farthest place of worship". Some modern scholars maintain that the earliest tradition saw this faraway site as a celestial twin of the Kaaba, so that Muhammad's journey took him directly from Mecca through the heavens. A later tradition, however, refers to it as Bayt al-Maqdis, which is generally associated with Jerusalem. Over time, these different traditions merged to present the journey as one that began in Mecca, passed through Jerusalem, and then ascended to heaven.[160]

The dating of the events also differs from account to account. Ibn Sa'd recorded that Muhammad's Mi'raj took place first, from near the Kaaba to the heavens, on the 27th of Ramadan, 18 months before the Hijrah, while the Isra' from Mecca to Bayt al-Maqdis took place on the 17th night of the Last Rabi’ul before the Hijrah. As is well known, these two stories were later combined into one. In Ibn Hisham's account, the Isra' came first and then the Mi'raj, and he put these stories before the deaths of Khadija and Abu Talib. In contrast, al-Tabari included only the story of Muhammad's ascension from the sanctuary in Mecca to "the earthly heaven". Tabari placed this story at the beginning of Muhammad's public ministry, between his account of Khadija becoming "the first to believe in the Messenger of God" and his account of "the first male to believe in the Messenger of God".[158]

Migration to Medina

As resistance to his proselytism in Mecca grew, Muhammad began to limit his efforts to non-Meccans who attended fairs or made pilgrimages.[161] During this period, Muhammad had an encounter with six individuals from the Banu Khazraj. These men had a history of raiding Jews in their locality, who in turn would warn them that a prophet would be sent to punish them. On hearing Muhammad's religious message, they said to each other, "This is the very prophet of whom the Jews warned us. Don't let them get to him before us!" Upon embracing Islam, they returned to Medina and shared their encounter, hoping that by having their people—the Khazraj and the Aws, who had been at odds for so long—accept Islam and adopt Muhammad as their leader, unity could be achieved between them.[162][163]

The next year, five of the earlier converts revisited Muhammad, bringing with them seven newcomers, three of whom were from the Banu Aws. At Aqaba, near Mecca, they pledged their loyalty to him.[162] Muhammad then entrusted Mus'ab ibn Umayr to join them on their return to Medina to promote Islam. Come June 622, a significant clandestine meeting was convened, again at Aqaba. In this gathering, seventy-five individuals from Medina (then Yathrib) attended, including two women, representing all the converts of the oases.[164] Muhammad asked them to protect him as they would protect their wives and children. They concurred and gave him their oath,[165] commonly referred to as the second pledge at al-Aqabah or the pledge of war. Paradise was Muhammad's promise to them in exchange for their loyalty.[166][167]

Subsequently, Muhammad called upon the Meccan Muslims to relocate to Medina.[164][168] This event is known as the Hijrah, literally meaning 'severing of kinship ties'.[169][170] The departures spanned approximately three months. To avoid arriving in Medina by himself with his followers remaining in Mecca, Muhammad chose not to go ahead and instead stayed back to watch over them and persuade those who were reluctant.[164] Some were held back by their families from leaving, but in the end, there were no Muslims left in Mecca.[171][172]

Islamic tradition recounts that in light of the unfolding events, Abu Jahl proposed a joint assassination of Muhammad by representatives of each clan. Having been informed about this by the angel Gabriel, Muhammad asked his cousin Ali to lie in his bed covered with his green hadrami mantle, assuring that it would safeguard him. That night, the group of planned assassins approached Muhammad's home to carry out the attack but changed their minds upon hearing the voices of Sawdah and some of Muhammad's daughters, since it was considered shameful to kill a man in front of the women in his family. They instead chose to wait until Muhammad left the house the next morning; one of the men peeked into a window and saw what he believed to be Muhammad (but was actually Ali dressed in Muhammad's cloak), though unbeknownst to them, Muhammad had previously escaped from the back of the residence. When Ali went outside to go for a walk the following morning, the men realized they had been fooled, and the Quraysh consequently offered a 100-camel bounty for the return of Muhammad's body, dead or alive.[173] After staying hidden for three days, Muhammad subsequently departed with Abu Bakr for Medina,[174] which at the time was still named Yathrib; the two men arrived in Medina on 4 September 622.[175] The Meccan Muslims who undertook the migration were then called the Muhajirun, while the Medinan Muslims were dubbed the Ansar.[176]

Medinan years

Building the religious community in Medina

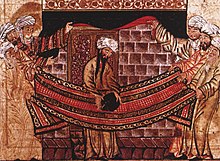

A few days after settling in Medina, Muhammad negotiated for the purchase of a piece of land; upon this plot, the Muslims began constructing a building that would become Muhammad's residence as well as a community gathering place (masjid) for prayer (salat). Tree trunks were used as pillars to hold up the roof, and there was no fancy pulpit; instead, Muhammad stood on top of a small stool to speak to the congregation. The structure was completed after about seven months in April 623, becoming the first Muslim building and mosque; its northern wall had a stone marking the direction of prayer (qibla) which was Jerusalem at that time. Muhammad used the building to host public and political meetings, as well as a place for the poor to gather to receive alms, food, and care. Christians and Jews were also allowed to participate in community worship at the mosque. Initially, Muhammad's religion had no organized way to call the community to prayer in a coordinated manner. To resolve this, Muhammad had considered using a ram's horn (shofar) like the Jews or a wooden clapper like the Christians, but one of the Muslims in the community had a dream where a man in a green cloak told him that someone with a loud booming voice should announce the service by crying out "allahu akbar" ('God is greater') to remind Muslims of their top priority; when Muhammad heard about this dream, he agreed with the idea and selected Bilal, a former Abyssinian slave known for his loud voice.[177]

Constitution of Medina

The Constitution of Medina was a legal covenant written by Muhammad. In the constitution, Medina's Arab and Jewish tribes promised to live peacefully alongside the Muslims and to refrain from making a separate treaty with Mecca. It also guaranteed the Jews freedom of religion. In the agreement, everyone under its jurisdiction was required to defend and protect the oasis if attacked. Politically, the agreement helped Muhammad better understand which people were on his side.[178] Ibn Ishaq, following his narration of the Hijrah, maintains that Muhammad penned the text and divulges its assumed content without supplying any isnad or corroboration.[179] The appellation is generally deemed imprecise, as the text neither established a state nor enacted Quranic statutes,[180] but rather addressed tribal matters.[181] While scholars from both the West and the Muslim world agree on the text's authenticity, disagreements persist on whether it was a treaty or a unilateral proclamation by Muhammad, the number of documents it comprised, the primary parties, the specific timing of its creation (or that of its constituent parts), whether it was drafted before or after Muhammad's removal of the three leading Jewish tribes of Medina, and the proper approach to translating it.[179][182]

Beginning of armed conflict

Following the emigration, the people of Mecca seized property of Muslim emigrants to Medina.[183] War would later break out between the people of Mecca and the Muslims. Muhammad delivered Quranic verses permitting Muslims to fight the Meccans.[184] According to the traditional account, on 11 February 624, while praying in the Masjid al-Qiblatayn in Medina, Muhammad received revelations from God that he should be facing Mecca rather than Jerusalem during prayer. Muhammad adjusted to the new direction, and his companions praying with him followed his lead, beginning the tradition of facing Mecca during prayer.[185]

Permission has been given to those who are being fought, because they were wronged. And indeed, Allah is competent to give them victory. Those who have been evicted from their homes without right—only because they say, "Our Lord is Allah." And were it not that Allah checks the people, some by means of others, there would have been demolished monasteries, churches, synagogues, and mosques in which the name of Allah is much mentioned. And Allah will surely support those who support Him. Indeed, Allah is Powerful and Exalted in Might.

Muhammad ordered a number of raids to capture Meccan caravans, but only the 8th of them, the Raid on Nakhla, resulted in actual fighting and capture of booty and prisoners.[24] In March 624, Muhammad led some three hundred warriors in a raid on a Meccan merchant caravan. The Muslims set an ambush for the caravan at Badr.[186] Aware of the plan, the Meccan caravan eluded the Muslims. A Meccan force was sent to protect the caravan and went on to confront the Muslims upon receiving word that the caravan was safe.[187] Due to being outnumbered more than three to one, a spirit of fear ran throughout the Muslim camp; Muhammad tried to boost their morale by telling them he had a dream in which God promised to send 1,000 angels to fight with them.[188][189] From a tactical standpoint, Muhammad placed troops in front of all of the wells so the Quraysh would have to fight for water, and positioned other troops in such a way that would require the Quraysh to fight uphill while also facing the sun.[188] The Battle of Badr commenced, and the Muslims ultimately won, killing at least forty-five Meccans with fourteen Muslims dead. They also succeeded in killing many Meccan leaders, including Abu Jahl.[190] Seventy prisoners had been acquired, many of whom were ransomed.[191][192][193] Muhammad and his followers saw the victory as confirmation of their faith[51] and Muhammad ascribed the victory to the assistance of an invisible host of angels. The Quranic verses of this period, unlike the Meccan verses, dealt with practical problems of government and issues like the distribution of spoils.[194]

The victory strengthened Muhammad's position in Medina and dispelled earlier doubts among his followers.[195] As a result, the opposition to him became less vocal. Pagans who had not yet converted were very bitter about the advance of Islam. Two pagans, Asma bint Marwan of the Aws Manat tribe and Abu 'Afak of the 'Amr b. 'Awf tribe, had composed verses taunting and insulting the Muslims. They were killed by people belonging to their own or related clans, and Muhammad did not disapprove of the killings. This report, however, is considered by some to be a fabrication.[196] Most members of those tribes converted to Islam, and little pagan opposition remained.[197]

Muhammad expelled from Medina the Banu Qaynuqa, one of three main Jewish tribes,[51] but some historians contend that the expulsion happened after Muhammad's death.[198] According to al-Waqidi, after Abd Allah ibn Ubayy spoke for them, Muhammad refrained from executing them and commanded that they be exiled from Medina.[199] Following the Battle of Badr, Muhammad also made mutual-aid alliances with a number of Bedouin tribes to protect his community from attacks from the northern part of Hejaz.[51]

Conflicts with Jewish tribes

Once the ransom arrangements for the Meccan captives were finalized, he initiated a siege on the Banu Qaynuqa,[200] regarded as the weakest and wealthiest of Medina's three main Jewish tribes.[201][202] Muslim sources provide different reasons for the siege, including an altercation involving Hamza and Ali in the Banu Qaynuqa market, and another version by Ibn Ishaq, which tells the story of a Muslim woman being pranked by a Qaynuqa goldsmith.[202][203] Regardless of the cause, the Banu Qaynuqa sought refuge in their fort, where Muhammad blockaded them, cutting off their access to food supplies. The Banu Qaynuqa requested help from their Arab allies, but the Arabs refused since they were supporters of Muhammad.[204] After roughly two weeks, the Banu Qaynuqa capitulated without engaging in combat.[201][202]

Following the surrender of the Qaynuqa, Muhammad was moving to execute the men of the tribe when Abdullah ibn Ubayy, a Muslim Khazraj chieftain who had been aided by the Qaynuqa in the past encouraged Muhammad to show leniency. In a narrated incident, Muhammad turned away from Ibn Ubayy, but undeterred, the chieftain grasped Muhammad's cloak, and refused to let go until Muhammad agreed to treat the tribe leniently. Despite being angered by the incident, Muhammad spared the Qaynuqa, stipulating that they must depart Medina within three days and relinquish their property to the Muslims, with a fifth (khums) being retained by Muhammad.[205][206]

Back in Medina, Ka'b ibn al-Ashraf, a wealthy half-Jewish man from Banu Nadir and staunch critic of Muhammad, had just returned from Mecca after producing poetry that mourned the death of the Quraysh at Badr and aroused them to retaliate.[207][208] When Muhammad learned of this incitement against the Muslims, he asked his followers, "Who is ready to kill Ka'b, who has hurt God and His apostle?"[209] Ibn Maslamah offered his services, explaining that the task would require deception. Muhammad did not contest this. He then gathered accomplices, including Ka'b's foster brother, Abu Naila. They pretended to complain about their post-conversion hardships, persuading Ka'b to lend them food. On the night of their meeting with Ka'b, they murdered him when he was caught off-guard.[210]

Meccan retaliation

In 625, the Quraysh, wearied by Muhammad's continuous attacks on their caravans, decided to take decisive action. Led by Abu Sufyan, they assembled an army to oppose Muhammad.[200][211] Upon being alerted by his scout about the impending threat, Muhammad convened a war council. Initially, he considered defending from the city center, but later decided to meet the enemy in open battle at Mount Uhud, following the insistence of the younger faction of his followers.[212] As they prepared to depart, the remaining Jewish allies of Abdullah ibn Ubayy offered their help, which Muhammad declined.[213] Despite being outnumbered, the Muslims initially held their ground but lost advantage when some archers disobeyed orders. As rumors of Muhammad's death spread, the Muslims started to flee, but he had only been injured and managed to escape with a group of loyal adherents. Satisfied they had restored their honor, the Meccans returned to Mecca.[200][214] Mass casualties suffered by the Muslims in the Battle of Uhud resulted in many wives and daughters being left without a male protector, so after the battle, Muhammad received revelation allowing Muslim men to have up to four wives each, marking the beginning of polygyny in Islam.[215]

Sometime later, Muhammad found himself needing to pay blood money to Banu Amir. He sought monetary help from the Jewish tribe of Banu Nadir,[216][217][218] and they agreed to his request.[217] However, while waiting, he departed from his companions and disappeared. When they found him at his home, according to Ibn Ishaq, Muhammad disclosed that he had received a divine revelation of a planned assassination attempt on him by the Banu Nadir, which involved dropping a boulder from a rooftop. Muhammad then initiated a siege on the tribe;[219][220] during this time he also commanded the felling and burning of their palm groves,[221] which was an unambiguous symbol of declaring war in Arabia.[222] After a fortnight or so, the Banu Nadir capitulated.[223] They were directed to vacate their land and permitted to carry only one camel-load of goods for every three people.[224] From the spoils, Muhammad claimed a fertile piece of land where barley sprouted amongst palm trees.[225]

Raid on the Banu Mustaliq

Upon receiving a report that the Banu Mustaliq were planning an attack on Medina, Muhammad's troops executed a surprise attack on them at their watering place, causing them to flee rapidly. In the confrontation, the Muslims lost one man, while the enemy suffered ten casualties.[226] As part of their triumph, the Muslims seized 2,000 camels, 500 sheep and goats, and 200 women from the tribe.[227] The Muslim soldiers desired the captive women, but they also sought ransom money. They asked Muhammad about using coitus interruptus to prevent pregnancy, to which Muhammad replied, "You are not under any obligation to forbear from that..."[228][229] Later, envoys arrived in Medina to negotiate the ransom for the women and children. Despite having the choice, all of them chose to return to their country instead of staying.[228][229]

Battle of the Trench

With the help of the exiled Banu Nadir, the Quraysh military leader Abu Sufyan mustered a force of 10,000 men. Muhammad prepared a force of about 3,000 men and adopted a form of defense unknown in Arabia at that time; the Muslims dug a trench wherever Medina lay open to cavalry attack. The idea is credited to a Persian convert to Islam, Salman the Persian. The siege of Medina began on 31 March 627 and lasted two weeks.[230] Abu Sufyan's troops were unprepared for the fortifications, and after an ineffectual siege, the coalition decided to return home.[231] The Quran discusses this battle in sura Al-Ahzab, in verses 33:9–27.[232] During the battle, the Jewish tribe of Banu Qurayza, located to the south of Medina, entered into negotiations with Meccan forces to revolt against Muhammad. Although the Meccan forces were swayed by suggestions that Muhammad was sure to be overwhelmed, they desired reassurance in case the confederacy was unable to destroy him. No agreement was reached after prolonged negotiations, partly due to sabotage attempts by Muhammad's scouts.[233] After the coalition's retreat, the Muslims accused the Banu Qurayza of treachery and besieged them in their forts for 25 days. The Banu Qurayza eventually surrendered; according to Ibn Ishaq, all the men apart from a few converts to Islam were beheaded, while the women and children were enslaved.[234][235] Walid N. Arafat and Barakat Ahmad have disputed the accuracy of Ibn Ishaq's narrative.[236] Arafat believes that Ibn Ishaq's Jewish sources, speaking over 100 years after the event, conflated this account with memories of earlier massacres in Jewish history; he notes that Ibn Ishaq was considered an unreliable historian by his contemporary Malik ibn Anas, and a transmitter of "odd tales" by the later Ibn Hajar.[237] Ahmad argues that only some of the tribe were killed, while some of the fighters were merely enslaved.[238][239] Watt finds Arafat's arguments "not entirely convincing", while Meir J. Kister has refuted the arguments of Arafat and Ahmad.[240]

In the siege of Medina, the Meccans exerted the available strength to destroy the Muslim community. The failure resulted in a significant loss of prestige; their trade with Syria vanished.[241] Following the Battle of the Trench, Muhammad made two expeditions to the north, both ended without any fighting.[51] While returning from one of these journeys (or some years earlier according to other early accounts), an accusation of adultery was made against Aisha, Muhammad's wife. Aisha was exonerated from accusations when Muhammad announced he had received a revelation confirming Aisha's innocence and directing that charges of adultery be supported by four eyewitnesses (sura 24, An-Nur).[242]

Invasion of the Banu Qurayza

On the day the Quraysh forces and their allies withdrew, Muhammad, while bathing at his wife's abode, received a visit from the angel Gabriel, who instructed him to attack the Jewish tribe of Banu Qurayza.[243][244][245] Islamic sources recount that during the preceding Meccan siege, the Quraysh leader Abu Sufyan incited the Qurayza to attack the Muslims from their compound, but the Qurayza demanded the Quraysh to provide 70 hostages from among themselves to ascertain their commitment to their plans, as proposed by Muhammad's secret agent Nuaym ibn Masud. Abu Sufyan refused their requirement.[246] Nevertheless, later accounts claim that 11 Jewish individuals from the Qurayza were indeed agitated and acted against Muhammad, though the course of event may have been dramatized within the tradition.[247][244]

Citing the intrigue of the Qurayza, Muhammad besieged the tribe, though the tribe denied the charges.[248][249][250] However, there are sources that say the Banu Qurayza broke the treaty with Muhammad and assisted the enemies of Muslims during the Battle of the Trench.[251][252][253] As the situation turned against the Qurayza, the tribe proposed to leave their land with one loaded camel each, but Muhammad refused. They then offered to leave without taking anything, but this was rejected as well, with Muhammad insisting on their unconditional surrender.[254][248] The Qurayza subsequently requested to confer with one of their Aws allies who had embraced Islam, leading to the arrival of Abu Lubaba. When asked about Muhammad's intentions, he gestured towards his throat, indicating an imminent massacre. He immediately regretted his indiscretion and tied himself to one of the Mosque pillars as a form of penance.[255][254]

After a 25-day siege, the Banu Qurayza surrendered. The Muslims of Banu Aws entreated Muhammad for leniency, prompting him to suggest that one of their own should serve as the judge, which they accepted. Muhammad assigned the role to Sa'd ibn Mu'adh, a man nearing death from an infection in his wounds from the previous Meccan siege.[256][255][257] He pronounced that all the men should be put to death, their possessions to be distributed among Muslims, and their women and children to be taken as captives. Muhammad approved this pronouncement saying it aligned with the God's judgement.[255][256] Consequently, 600–900 men of Banu Qurayza were executed. The women and children were distributed as slaves, with some being transported to Najd to be sold. The proceeds were then utilized to purchase weapons and horses for the Muslims.[258]

Incidents with the Banu Fazara

A few months after the conflict with the Banu Qurayza, Muhammad organized a caravan to conduct trade in Syria. Zayd ibn Haritha was tasked with guarding the convoy. When they journeyed through the territory of Banu Fazara, whom Zayd had raided in the past, the tribe seized the opportunity for revenge, attacking the caravan and injuring him. Upon his return to Medina, Muhammad ordered Zayd to lead a punitive operation against the Fazara in which their matriarch Umm Qirfa was captured and brutally executed.[259][260]

Treaty of Hudaybiyya

Early in 628, following a dream of making an unopposed pilgrimage to Mecca, Muhammad embarked on the journey. He was dressed in his customary pilgrim attire and was accompanied by a group of followers.[262] Upon reaching Hudaybiyya, they encountered Quraysh emissaries who questioned their intentions. Muhammad explained they had come to venerate the Kaaba, not to fight.[263] He then sent Uthman, Abu Sufyan's second cousin, to negotiate with the Quraysh. As the negotiations were prolonged, rumors of Uthman's death began to spark, prompting Muhammad to call his followers to renew their oaths of loyalty. Uthman returned with news of a negotiation impasse. Muhammad remained persistent. In the end, the Quraysh sent Suhayl ibn Amr, an envoy with full negotiation powers. Following lengthy discussions, a treaty was finally enacted,[264] with terms:

- A ten-year truce was established between both parties.

- If a Qurayshite came to Muhammad's side without his guardian's allowance, he was to be returned to the Quraysh; yet, if a Muslim came to the Quraysh, he would not be surrendered to Muhammad.

- Any tribes interested in forming alliances with Muhammad or the Quraysh were free to do so. These alliances were also protected by the ten-year truce.

- Muslims were then required to depart back to Medina, however, they were permitted to make the Umrah pilgrimage in the coming year.[264][263]

Invasion of Khaybar

Roughly ten weeks subsequent to his return from Hudaybiyya, Muhammad expressed his plan to invade Khaybar, a flourishing oasis about 75 miles (121 km) north of Medina. The city was populated by Jews, including those from the Banu Nadir, who had previously been expelled by Muhammad from Medina. With the prospect of rich spoils from the mission, numerous volunteers answered his call.[265][266] To keep their movements hidden, the Muslim military chose to march during the nighttime. As dawn arrived and the city folks stepped out of their fortifications to harvest their dates, they were taken aback by the sight of the advancing Muslim forces. Muhammad cried out, "Allahu Akbar! Khaybar is destroyed. For when we approach a people's land, a terrible morning awaits the warned ones."[267] After a strenuous battle lasting more than a month, the Muslims successfully captured the city.[268]

The spoils, inclusive of the wives of the slain warriors, were distributed among the Muslims.[269] The chief of the Jews, Kenana ibn al-Rabi, to whom the treasure of Banu al-Nadir was entrusted, denied knowing its whereabouts. After a Jew disclosed his habitual presence around a particular ruin, Muhammad ordered excavations, and the treasure was found. When questioned about the remaining wealth, Kenana refused to divulge it. Kinana was then put through torture by Muhammad's decree and subsequently beheaded by Muhammad ibn Maslamah in revenge for his brother.[270][271] Muhammad took Kinana's wife, Safiyya bint Huyayy, as his own slave and later advised her to convert to Islam. She accepted and agreed to become Muhammad's wife.[272]

Following their defeat by the Muslims, some of the Jews proposed to Muhammad that they stay and serve as tenant farmers, given the Muslims' lack of expertise and labor force for date palm cultivation. They agreed to give half of the annual produce to the Muslims. Muhammad consented to this arrangement with the caveat that he could displace them at any time. While they were allowed to farm, he demanded the surrender of all gold or silver, executing those who secreted away their wealth.[273][274] Taking a cue from what transpired in Khaybar, the Jews in Fadak immediately sent an envoy to Muhammad and agreed to the same terms of relinquishing 50% of their annual harvest. However, since no combat occurred, the rank and file had no claim to a portion of the spoils. Consequently, all the loot became Muhammad's exclusive wealth.[275][276]

At the feast following the battle, the meal served to Muhammad was reportedly poisoned. His companion, Bishr, fell dead after consuming it, while Muhammad himself managed to vomit it out after tasting it.[275][277] The perpetrator was Zaynab bint al-Harith, a Jewish woman whose father, uncle, and husband had been killed by the Muslims.[271] When asked why she did it, she replied, "You know what you've done to my people... I said to myself: If he is truly a prophet, he will know about the poison. If he's merely a king, I'll be rid of him."[275][271] Muhammad suffered illness for a period due to the poison he ingested, and he endured sporadic pain from it until his death.[278][279]

Final years

Conquest of Mecca

The truce of Hudaybiyyah was enforced for two years. The tribe of Banu Khuza'ah had good relations with Muhammad, whereas their enemies, the Banu Bakr, had allied with the Meccans. A clan of the Bakr made a night raid against the Khuza'ah, killing a few of them. The Meccans helped the Banu Bakr with weapons and, according to some sources, a few Meccans also took part in the fighting. After this event, Muhammad sent a message to Mecca with three conditions, asking them to accept one of them. These were: either the Meccans would pay blood money for the slain among the Khuza'ah tribe, they disavow themselves of the Banu Bakr, or they should declare the truce of Hudaybiyyah null.[280][281]

The Meccans replied that they accepted the last condition.[280] Soon they realized their mistake and sent Abu Sufyan to renew the Hudaybiyyah treaty, a request that was declined by Muhammad.

Muhammad began to prepare for a campaign.[282] In 630, Muhammad marched on Mecca with 10,000 Muslim converts. With minimal casualties, Muhammad seized control of Mecca.[283] He declared an amnesty for past offences, except for ten men and women who were "guilty of murder or other offences or had sparked off the war and disrupted the peace".[284] Some of these were later pardoned[285] Most Meccans converted to Islam and Muhammad proceeded to destroy all the statues of Arabian gods in and around the Kaaba.[286] According to reports collected by Ibn Ishaq and al-Azraqi, Muhammad personally spared paintings or frescos of Mary and Jesus, but other traditions suggest that all pictures were erased.[287] The Quran discusses the conquest of Mecca.[232][288]

Subduing the Hawazin and Thaqif and the expedition to Tabuk

Upon learning that Mecca had fallen to the Muslims, the Banu Hawazin gathered their entire tribe, including their families, to fight. They are estimated to have around 4,000 warriors.[289][290] Muhammad led 12,000 soldiers to raid them, but they surprised him at the valley of Hunayn.[291] The Muslims overpowered them and took their women, children and animals.[292] Muhammad then turned his attention to Taif, a city that was famous for its vineyards and gardens. He ordered them to be destroyed and besieged the city, which was surrounded by walls. After 15–20 days of failing to breach their defenses, he abandoned the attempts.[293][294]

When he divided the plentiful loot acquired at Hunayn among his soldiers, the rest of the Hawazin converted to Islam[295] and implored Muhammad to release their children and women, reminding him that he had been nursed by some of those women when he was a baby. He complied but held on to the rest of the plunder. Some of his men opposed giving away their portions, so he compensated them with six camels each from subsequent raids.[296] Muhammad distributed a big portion of the booty to the new converts from the Quraysh. Abu Sufyan and two of his sons, Mu'awiya and Yazid, got 100 camels individually.[297][298] The Ansar, who had fought bravely in the battle, but received close to nothing, were unhappy with this.[299][300] One of them remarked, "It is not with such gifts that one seeks God's face." Disturbed by this utterance, Muhammad retorted, "He changed color."[297]

Roughly 10 months after he captured Mecca, Muhammad took his army to attack the wealthy border provinces of Byzantine Syria. Several motives are proposed, including avenging the defeat at Mu'tah and earning vast booty.[301][302] Because of the drought and severe heat at that time, some of the Muslims refrained from participating. This led to the revelation of Quran 9:38 which rebuked those slackers.[303] When Muhammad and his army reached Tabuk, there were no hostile forces present.[304] However, he was able to force some of the local chiefs to accept his rule and pay jizya. A group under Khalid ibn Walid that he sent for a raid also managed to acquire some booty including 2,000 camels and 800 cattle.[305]

The Hawazin's acceptance of Islam resulted in Taif losing its last major ally.[306] After enduring a year of unrelenting thefts and terror attacks from the Muslims following the siege, the people of Taif, known as the Banu Thaqif, finally reached a tipping point and acknowledged that embracing Islam was the most sensible path for them.[307][308][309]

Farewell pilgrimage

On February 631, Muhammad received a revelation granting idolaters four months of grace, after which the Muslims would attack, kill, and plunder them wherever they met.[310][311]

During the 632 pilgrimage season, Muhammad personally led the ceremonies and gave a sermon. Among the key points highlighted are said to have been the prohibition of usury and vendettas related to past murders from the pre-Islamic era; the brotherhood of all Muslims; and the adoption of twelve lunar months without intercalation.[312][313]

Death

After praying at the burial site in June 632, Muhammad suffered a dreadful headache that made him cry in pain.[314] He continued to spend the night with each of his wives one by one,[315] but he fainted in Maymunah's hut.[316] He requested his wives to allow him to stay in Aisha's hut. He could not walk there without leaning on Ali and Fadl ibn Abbas, as his legs were trembling. His wives and his uncle al-Abbas fed him an Abyssinian remedy when he was unconscious.[317] When he came to, he inquired about it, and they explained they were afraid he had pleurisy. He replied that God would not afflict him with such a vile disease, and ordered all the women to also take the remedy.[318] According to various sources, including Sahih al-Bukhari, Muhammad said that he felt his aorta being severed because of the food he ate at Khaybar.[319][279] On 8 June 632, Muhammad died.[320][321] In his last moments, he reportedly uttered:

O God, forgive me and have mercy on me; and let me join the highest companions.[322][323][324]

— Muhammad

Historian Alfred T. Welch speculates that Muhammad's death was caused by Medinan fever, which was aggravated by physical and mental fatigue.[325]

Tomb

Muhammad was buried where he died in Aisha's house.[51][326][327] During the reign of the Umayyad caliph al-Walid I, the Prophet's Mosque was expanded to include the site of Muhammad's tomb.[328] The Green Dome above the tomb was built by the Mamluk sultan Al Mansur Qalawun in the 13th century, although the green color was added in the 16th century, under the reign of Ottoman sultan Suleiman the Magnificent.[329] Among tombs adjacent to that of Muhammad are those of his companions (Sahabah), the first two Muslim caliphs Abu Bakr and Umar, and an empty one that Muslims believe awaits Jesus.[327][330][331]

When Saud bin Abdul-Aziz took Medina in 1805, Muhammad's tomb was stripped of its gold and jewel ornamentation. Adherents to Wahhabism, Saud's followers, destroyed nearly every tomb dome in Medina in order to prevent their veneration,[332] and the one of Muhammad is reported to have narrowly escaped.[333] Similar events took place in 1925, when the Saudi militias retook—and this time managed to keep—the city.[334][335][336] In the Wahhabi interpretation of Islam, burial is to take place in unmarked graves.[333] Although the practice is frowned upon by the Saudis, many pilgrims continue to practice a ziyarat—a ritual visit—to the tomb.[337][338]

Succession

With Muhammad's death, disagreement broke out over who his successor would be.[320][321] Umar ibn al-Khattab, a prominent companion of Muhammad, nominated Abu Bakr, Muhammad's friend and collaborator. With additional support, Abu Bakr was confirmed as the first caliph. This choice was disputed by some of Muhammad's companions, who held that Ali ibn Abi Talib, his cousin and son-in-law, had been designated the successor by Muhammad at Ghadir Khumm. Abu Bakr immediately moved to strike against the forces of the Byzantine Empire because of the previous defeat, although he first had to put down a rebellion by Arab tribes in an event that Muslim historians later referred to as the Ridda wars, or "Wars of Apostasy".[339]

The pre-Islamic Middle East was dominated by the Byzantine and Sasanian empires. The Roman–Persian Wars between the two had devastated the region, making the empires unpopular amongst local tribes. Furthermore, in the lands that would be conquered by Muslims, many Christians (Nestorians, Monophysites, Jacobites and Copts) were disaffected from the Eastern Orthodox Church which deemed them heretics. Within a decade Muslims conquered Mesopotamia, Byzantine Syria, Byzantine Egypt,[340] large parts of Persia, and established the Rashidun Caliphate.

Household

Muhammad's life is traditionally defined into two periods: pre-hijra in Mecca (570–622), and post-hijra in Medina (622–632). Muhammad is said to have had thirteen wives in total (although two have ambiguous accounts, Rayhana bint Zayd and Maria al-Qibtiyya, as wife or concubine[h][341]).

At the age of 25, Muhammad married the wealthy Khadija who was 40 years old.[342] The marriage lasted for 25 years and was a happy one.[343] Muhammad did not enter into marriage with another woman during this marriage.[344][345] After Khadija's death, Khawla bint Hakim suggested to Muhammad that he should marry Sawdah bint Zam'ah, a Muslim widow, or Aisha, daughter of Umm Ruman and Abu Bakr of Mecca. Muhammad is said to have asked for arrangements to marry both.[242] According to classical sources, Muhammad married Aisha when she was 6–7 years old; the marriage was consummated later, when she was 9 years old and he was 53 years old.[346]

Muhammad performed household chores such as preparing food, sewing clothes, and repairing shoes. He is also said to have had accustomed his wives to dialogue; he listened to their advice, and the wives debated and even argued with him.[347][348]

Khadija is said to have had four daughters with Muhammad (Ruqayya bint Muhammad, Umm Kulthum bint Muhammad, Zainab bint Muhammad, Fatimah Zahra) and two sons (Abd Allah ibn Muhammad and Qasim ibn Muhammad, who both died in childhood). All but one of his daughters, Fatimah, died before him.[349] Some Shia scholars contend that Fatimah was Muhammad's only daughter.[350] Maria al-Qibtiyya bore him a son named Ibrahim ibn Muhammad, who died at two years old.[349]

Nine of Muhammad's wives survived him.[341] Aisha, who became known as Muhammad's favorite wife in Sunni tradition, survived him by decades and was instrumental in helping assemble the scattered sayings of Muhammad that form the hadith literature for the Sunni branch of Islam.[242]

Zayd ibn Haritha was a slave that Khadija gave to Muhammad. He was bought by her nephew Hakim ibn Hizam at the market in Ukaz.[351] Zayd then became the couple's adopted son, but was later disowned when Muhammad was about to marry Zayd's ex-wife, Zaynab bint Jahsh.[352] According to a BBC summary, "the Prophet Muhammad did not try to abolish slavery, and bought, sold, captured, and owned slaves himself. But he insisted that slave owners treat their slaves well and stressed the virtue of freeing slaves. Muhammad treated slaves as human beings and clearly held some in the highest esteem".[353]

Legacy

Islamic tradition

Following the attestation to the oneness of God, the belief in Muhammad's prophethood is the main aspect of the Islamic faith. Every Muslim proclaims in the Shahada: "I testify that there is no god but God, and I testify that Muhammad is a Messenger of God". The Shahada is the basic creed or tenet of Islam. Islamic belief is that ideally the Shahada is the first words a newborn will hear; children are taught it immediately and it will be recited upon death. Muslims repeat the shahadah in the call to prayer (adhan) and the prayer itself. Non-Muslims wishing to convert to Islam are required to recite the creed.[354]

In Islamic belief, Muhammad is regarded as the last prophet sent by God.[356] Writings such as hadith and sira attribute several miracles or supernatural events to Muhammad.[357] One of these is the splitting of the Moon, which according to earliest available tafsir compilations is a literal splitting of the Moon.[358]

The sunnah represents the actions and sayings of Muhammad preserved in hadith and covers a broad array of activities and beliefs ranging from religious rituals, personal hygiene, and burial of the dead to the mystical questions involving the love between humans and God. The Sunnah is considered a model of emulation for pious Muslims and has to a great degree influenced the Muslim culture. Many details of major Islamic rituals such as daily prayers, the fasting and the annual pilgrimage are only found in the sunnah and not the Quran.[359]

Muslims have traditionally expressed love and veneration for Muhammad. Stories of Muhammad's life, his intercession and of his miracles have permeated popular Muslim thought and poetry (naʽat). Among Arabic odes to Muhammad, Qasidat al-Burda ("Poem of the Mantle") by the Egyptian Sufi al-Busiri (1211–1294) is particularly well-known, and widely held to possess a healing, spiritual power.[360] The Quran refers to Muhammad as "a mercy (rahmat) to the worlds".[361][51] The association of rain with mercy in Oriental countries has led to imagining Muhammad as a rain cloud dispensing blessings and stretching over lands, reviving the dead hearts, just as rain revives the seemingly dead earth.[i][51] Muhammad's birthday is celebrated as a major feast throughout the Muslim world, excluding Wahhabi-dominated Saudi Arabia where these public celebrations are discouraged.[362] When Muslims say or write the name of Muhammad, they usually follow it with the Arabic phrase ṣallā llahu ʿalayhi wa-sallam (may God honor him and grant him peace) or the English phrase peace be upon him.[363] In casual writing, the abbreviations SAW (for the Arabic phrase) or PBUH (for the English phrase) are sometimes used; in printed matter, a small calligraphic rendition is commonly used (ﷺ).

Appearance and depictions

Various sources present a probable description of Muhammad in the prime of his life. He was slightly above average in height, with a sturdy frame and wide chest. His neck was long, bearing a large head with a broad forehead. His eyes were described as dark and intense, accentuated by long, dark eyelashes. His hair, black and not entirely curly, hung over his ears. His long, dense beard stood out against his neatly trimmed mustache. His nose was long and aquiline, ending in a fine point. His teeth were well-spaced. His face was described as intelligent, and his clear skin had a line of hair from his neck to his navel. Despite a slight stoop, his stride was brisk and purposeful.[364] Muhammad's lip and cheek were ripped by a slingstone during the Battle of Uhud.[365][366] The wound was later cauterized, leaving a scar on his face.[367]